|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Alumni Profiles

Grateful for a MiracleBy Janice Harayda '70

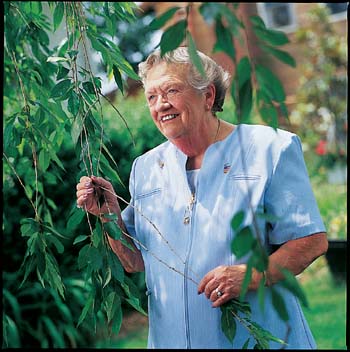

Photo by Paul Fetters

Photo by Paul Fetters

|

Ruth Goldthwait Maynard '52 bounds out of her car wearing a bright pink top and a smile to match and greets a visitor at the bus station in downtown Wilmington, Dela. Several years ago, she and her husband, Dan '52, toured the East Coast from Delaware to Florida. Two years ago, she attended her 50th Reunion in Durham.

Until a few years ago, none of the above would have been possible for Maynard. For 28 years, she suffered from agoraphobia, a condition that made it impossible for her to perform such tasks as holding a job, driving a car or even going to the grocery store.

Agoraphobia is an intense fear of places or situations that might be hard to escape or that lead to feelings of panic. People typically develop it between the ages of 18 and 54, and the National Institute of Mental Health says it affects 2.2 percent of that age group. No one knows what causes it—heredity, environment, or both—although it often develops when people who have panic attacks start to avoid the sites of the attacks. One of the most baffling aspects of the condition is that it often afflicts cheerful and outgoing people like Maynard, longtime secretary of the Class of '52 who always signs her columns, "God bless you all!"

In 1952 after she and Dan married, they settled in Newark, Dela., where Dan worked as an engineer for DuPont. Ruth worked as a crossing guard while they reared their children, Daniel and Kristine. One day while on duty at a crosswalk, Maynard had the classic signs of a panic attack, including a pounding heart, racing pulse and sweating palms. She thought she was having a heart attack. Terrified, she began to avoid the crosswalk, then other public places.

"I started to have panic attacks everywhere," Maynard recalls. "The only place I could find security was at home. I just couldn't go anywhere. It was quite devastating, because I love life. And I didn't know what was wrong."

The panic attacks forced Maynard to quit work and give up all social activities. But as the years passed, she began to hope that help could be found. Watching a Baltimore talk show about agoraphobia hosted by the then little-known Oprah Winfrey, she learned about an anxiety-disorders clinic. Maynard enrolled in two 10-week behavior therapy programs with Dr. Robert L. DuPont, founding president of the Anxiety Disorders Association of America, who taught her techniques such as wearing a rubber band on her wrist and snapping it to distract herself from panic attacks. She practiced the techniques daily for years until finally, she was leading a life free of agoraphobia.

Now Maynard is enjoying pleasures she missed for decades—going to restaurants, taking her beloved grandchildren to see Disney on Ice, planning cruises to Bermuda. When she made a speech at her 50th Reunion, her UNH classmates gave her a standing ovation.

After remaining silent about her condition for so long, Maynard still finds it hard to talk about it. But because she would love to help others the way Oprah helped her, she is trying to overcome her reticence.

"If I can give back to even one human being, it will be worth it," she says. "People ask me if I feel bitter that I lost 28 years to agoraphobia. I don't. I just feel so grateful to be living a normal life again. It's a miracle."

Easy to print versionblog comments powered by Disqus