|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

Small SciencePage 2 of 5

"We talk about it all the time—how exciting it is that we are coming in and doing this research in such a cool and exciting field," says Garnsey. "We don't think, 'Maybe we're going to make a nanotube today.' We think, 'This is something that will become important and we're in at the start.'"

Interest has even spread outside the physical sciences—the Nano Group includes several economists and business specialists who are studying the rise of this potentially revolutionary technology in hopes of helping industry use it.

|

"Right now, we're hoping to get in on the ground floor of tracking and anticipating its development and its effect on industry and the economy," says Christine Shea, associate professor of operations management.

"A few years ago, people hadn't even heard the word 'nanotechnology,'" says Shea. "It's useful to look at it as a general purpose technology—sort of like electricity or the semiconductor. It's difficult to make generalizations about its overall effect, but in its applications the effect could range from incremental to radical."

There's a lot of nanoscale research going on at UNH, but things really got kicked up a notch this summer when the National Science Foundation rewarded UNH's ongoing collaboration with UMass-Lowell and Northeastern University by giving the trio a five-year, $12.4 million grant to create the Center for High-Rate Nanomanufacturing.

|

The grant puts UNH in a position to become prominent in the field, says Miller. "We've created a new paradigm by putting the strengths of each institution together. It's a pretty potent package. And I think this is the first multi-university center where all the schools are equal partners."��

The general model for the center is that UNH will concentrate on the basic science—the chemistry, physics and materials engineering needed to manipulate molecules to create Feynman-pleasing devices—while Lowell will emphasize high-speed manufacturing processes, and Northeastern will take the lead in reliability testing and modeling.

The duties will overlap extensively, however, and all three will also be studying the societal impact of nanotechnology and handling outreach to public schools as well as the Boston Museum of Science.

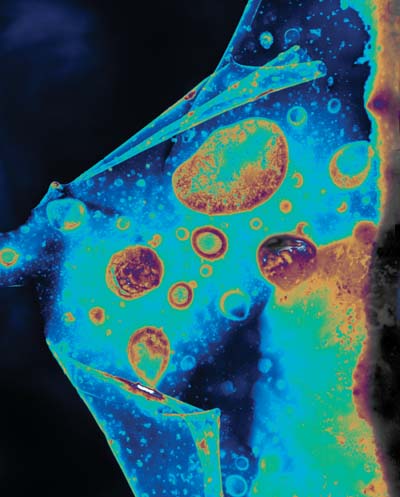

The center has two goals. One is to create working devices, including a nanotube memory chip that will—scientists hope—have substantially higher density, and therefore more memory, than existing silicon chips. The researchers are collaborating with the high-tech Massachusetts firm Nantero on the chip project and with New England-based Triton Systems on the development of another device, a nanosized biosensor. The biosensor will, in theory, be able to spot disease at an early stage by using immobilized antibodies to detect specific disease-related antigens.

Page: < Prev 1 2 3 4 5 Next >Easy to print version