|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

Street SmartPage 3 of 3

He enjoys shifting roles—attending a celebrity wine-and-cheese book signing one night and cruising the streets of Dorchester in a police car the next. He's worked as a bouncer in a Boston night club and also spent five summers as an assistant to the golf professional at the Hyannisport Club. "I can say 'terrific' without moving my mouth," he claims.

More recently, he has been hobnobbing in Beverley Hills, talking about his idea for a TV series that he summarizes as, "Kids are dying. Probation officer goes out on the streets. Kids aren't dying." Stewart, a dedicated movie fan, shared his idea with Howard Baldwin, former owner of the Hartford Whalers and the Pittsburg Penguins ice hockey teams and now a movie producer. Baldwin offered him a contract and is shopping for a network.

BRUSH YOUR TEETH

On a warm night in October, Stewart rides in the back of an unmarked car with three Mattapan officers. Two of them are wearing shorts. The bulging bulletproof vests under their T-shirts somehow make their bare knees look especially vulnerable. All of them watch the street but keep an ear tuned to the Red Sox game on the radio.

A laptop propped between the car's front seats gives them access to a database, letting them quickly run license plates and check the criminal status of anyone they might encounter.

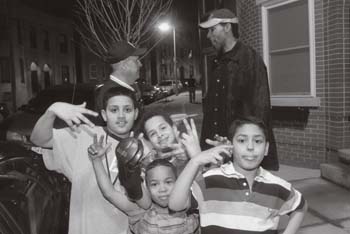

HAND TO HAND: Boston officials didn't realize that probation officers have greater powers than police when it comes to youth on probation until Bill Stewart '73 (right, with Boston police officer Sgt. Mike Kearn, left) did the legal research.

HAND TO HAND: Boston officials didn't realize that probation officers have greater powers than police when it comes to youth on probation until Bill Stewart '73 (right, with Boston police officer Sgt. Mike Kearn, left) did the legal research.

|

It's after 9 p.m. and Stewart has been at work since 8 a.m. He is currently assigned to domestic violence, but since Nite Lite is now part of every probation officer's job, he helps out from time to time and tonight he has the names and addresses of three youths on probation he plans to visit.

Before going to the clients' apartments, they cruise the neighborhood, observing who is hanging on what corners, and looking for a fellow named Smoke. The young officer behind the wheel must have learned to drive in Boston. He turns corners from the wrong lanes, never stops at stop signs, makes U-turns wherever he wants and backs up fast. They glide to the curb next to Smoke and two other men.

"Hey, s'up?" calls Stewart.

"Nothin'. S'up you?" Smoke answers, rolling back on his heels and smiling. One of his friends takes a couple of steps backward and watches. He's not smiling. The third man continues walking, but is brought back to the little gathering by one of the officers.

Stewart tells Smoke he really should brush his teeth, which is his way of saying he can smell beer on his breath. Smoke gives up his brown paper bag and the open quart of Heineken it holds. He also gives up a small quantity of marijuana that Stewart later throws out the window of the police car. Everything is cordial and routine, although everyone knows there could have been a bust. "Now Smoke owes us," says Stewart when they're back in the car.

No one is home at the curfew check: a dark triple-decker flat. At the next stop, a woman who answers the door downstairs says the family they are looking for has moved, and, no, she doesn't know where they went.

At the third apartment, a shirtless man comes to the door. He's wearing a belt with a three-inch, rhinestone-dollar-sign belt buckle. The belt has no relation to the jeans that ride low on the man's hips. Stewart asks him how it's goin,' checks his fingers for marijuana stains and bids him a good night.

The police bring Stewart back to his own car, and he heads off to one of his favorite restaurants, where he talks on the street corner for 20 minutes with the restaurant owner and a couple of other friends before eating dinner. He leaves the restaurant at 11 p.m. He'll be back at work at 8 the next morning.

|

One of the main reasons for the success of the "Boston Strategy," a collection of programs designed to reduce youth violence created in the 1990s, is that it built collaboration among probation officers, police, judges, street workers and religious leaders. Eventually, teachers, business leaders, academics and politicians also were engaged in the strategy. At its core was a goal to reestablish safe neighborhoods, rather than focus on offenders.

The strategy's success can be documented by a sharp and steady decline in Boston homicides—from 152 in 1990, including 16 under age 17, to 98 in 1995, with nine victims under age 17, and no youth deaths among the 43 homicides in 1997. There's been an increase in homicide rates in Boston in the last few years—61 in 2004, including seven under the age of 17, and 75 in 2005, including nine who were 17 or younger.

Stewart attributes the rise in street homicides among youth in the past couple of years to several factors: increased availability of guns; the coming of age of children with problems connected to their parents' crack use; the lack of fathers in many homes; the return to the streets of prison-smart men Stewart helped to send to jail; and a change in Washington, D.C. The year "2000 was a benchmark," he says. "The Democrats left office, the Republicans came in and federal programs started to slide, then the kids, entitlement programs, started to slide and so did the communities. It's a cyclical thing, in my opinion."

But he believes the Boston Strategy, especially Nite Light, has worked and can continue to work. He cites complaints filed concerning people on probation—12,000 in 1990 down to 9,000 in 2000.

A number of cities are using the strategy as a model. Stewart alone has talked about the strategy with more than 60 groups around the nation. Posted from the ceiling to the floor on one wall in his small office in the Dorchester District Court building are postcards from every place he has spoken. "I like to think there is at least one kid still alive in each of those cities because of Nite Lite," he says.

For a description of the Boston strategy, see http://ojjdp.ncjrs.org/pubs/gun_violence/profile02.html.

C.W. Wolff is a freelance writer and editor who lives in Kittery, Maine.

Page: < Prev 1 2 3Easy to print version

blog comments powered by Disqus