|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

Into the WoodsPage 3 of 3

TAKE NOTE: Mike Simmons '07, left, and Noah Hoffman '07 pause during a Thompson School class.

TAKE NOTE: Mike Simmons '07, left, and Noah Hoffman '07 pause during a Thompson School class.

|

"SINGLE BUCKERS, HERE'S your start," yells Quigley. The professor-turned-emcee is standing in a dirt parking lot just off UNH's Spinney Lane. It is a Saturday morning and the annual intercollegiate woodsmen competition is underway. Russell Orzechowki '08 steps in front of a giant pine log, sap still oozing from the freshly cut ends. His six-foot bucksaw, just like ones used more than a century ago to fell trees, is poised, glinting in the morning sun. "Timers ready?" shouts Quigley. "Competitors ready? Three. Two. One. Go!" Orzechowski is instantly in motion, pushing and pulling his blade in long fluid motions, without a single "snag." In 19 seconds—his best time ever—Orzechowski has sliced straight through the 18-inch log, lopping a piece off the end and winning the event.

"Nicely done," shouts a voice from the crowd. Turns out it's Orzechowski's father, Peter '77, who has come to cheer for his son. Standing next to Peter is his dad, Russell's grandfather, Stanley '50. While they've never been professional loggers, the family has done plenty of chopping and splitting through the years to feed the wood fires that help to heat their home. And Peter himself competed on the UNH woodsmen team a generation ago, when he was a student.

As for Russell, who is captain of this year's team, he likes being part of a tradition that goes beyond even his own family. "People used to work every day with these tools," he says. "Trying it, you really appreciate how difficult it is."

Students on the woodsmen team mill timber for their competitions and practices right on campus at the university's vintage sawmill, which has played an important role in the school's forestry programs since its construction in 1960. Today, the mill, with its upcoming renovations, has become a sort of tangible metaphor for the changes underway in the industry.

One hundred years ago forestry was an incredibly wasteful industry, according to Sarah Smith '78, a specialist with the UNH Cooperative Extension. "Now every dollar mill owners spend goes to improve the utilization of every tree." Bark, sawdust and chips—it all used to be considered waste. These days, bark is highly valued for mulch, sawdust goes to wood energy plants and chips go to pulp mills. Among other upgrades, UNH's renovated mill will include a new band saw. The thinner blade will produce less waste, which means more timber—about12 percent more board feet—can be milled from each log. "This means a better use of the resource," says Quigley, "which means, ultimately, fewer trees need to be cut."

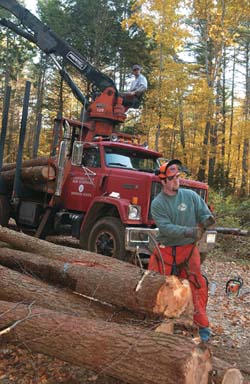

LOG ON: At the Woodman Farm log landing, Zack Chase '06 readies trees for a logging truck.

LOG ON: At the Woodman Farm log landing, Zack Chase '06 readies trees for a logging truck.

|

Better use of resources means more than an improved bottom line for sawmills fighting to survive in a competitive industry. With development pressures ever on the rise (New Hampshire's population almost doubled in size in just 10 years to 2.5 million in 2000) careful land use planning is critical—and the need for well-trained foresters has never been greater. "People no longer feel a connection to the land," says Sean Sullivan of the timberland owners' association. The days of working in the woods with bucksaw and axe are gone forever—and the tradition of passing land on from one generation to the next is dwindling, too, as children move away. New Hampshire alone loses about 17,500 acres of forestland every year, according to the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests.

Good foresters—people with a knowledge of today's high-tech tools, a commitment to sustainability, and an understanding of the historical importance of the land and the complexity inherent in its many valuable uses—can help change that trend. They can help people to view forestland as a forester does, as a living money market fund that, if carefully managed, can provide a source of income through the years as trees are selectively cut and harvested. "Our studies show that if landowners hold onto their land, rather than selling out to developers," says Sullivan, "they can, in the long run, make more money. But people need to be educated to view their land differently."

Within the tourism, land protection and forestry industries there are promising signs of change, as awareness grows that these constituencies are not at odds with one another; rather they share a common goal of maintaining a forest landscape. These days, when land is set aside for protection, it's likely that parts of it will actually be managed for timber.

"Our forestry alums can make a huge difference just in the little things they do every day in their jobs," says Ducey, who likes to point out that lots of people are willing to chop down trees. But foresters are the ones who take the long view, so that we have all the things that go with a well-managed forest: good drinking water, wildlife habitat, recreational resources.

ONE AFTERNOON AS he is winding up his work in the woods, Jake Bronnenberg pauses to examine a small black birch, about four inches in diameter. Growing around it is a cluster of fluttering hemlocks, trees so fragile-looking they seem almost inconsequential. But the hemlocks, Bronnenberg explains, protect the birch simply by shading it from the sun, preventing the sprouting of buds along the trunk. Eventually, the tree will grow into a good veneer tree, without any knots, highly valuable and ready for harvest.

Forestry students learn something of the ways of Mother Nature, gaining respect for the mystery of the land and the things that grow out of it. They know that their livelihood, more than most, will be tied, literally, to a precious natural resource—one they themselves will have a role in protecting. With this knowledge, comes a sort of long-term vision—an understanding that a well-managed forest, full of trees that grow straight and true, takes a long, long time to come to fruition. Forestry students, then, perhaps more than most, will be inclined to leave their impact on the world with this same awareness: that what they do with their careers, and the decisions they make along the way, will matter for a very long time to come.

by James Haney

by James Haney

|

Question: What has 3,800 acres spread across 28 different properties with miles of trails open to the public? Answer: The University of New Hampshire. The university's woodlands and natural areas, many of them heavily forested, may be one of the best-kept secrets in the state. But Steve Eisenhaure '93, '04, '06G, UNH's woodlands manager, hopes that'll change. "I want people to get out and use them," he says. "These are great properties."

While UNH's woodland areas provide valuable acreage for education and research, these lands also help to fulfill the university's outreach mission, providing open space for public use. Properties with maintained trails can be used for hiking, mountain biking, cross-country skiing, snowmobiling and more.

Some properties are close to UNH and well known, like College Woods and Foss Farm in Durham, and Mendum's Pond in Barrington. Farther afield, West Rattlesnake Mountain on Squam Lake offers "an awesome overlook of the lake," says Eisenhaure. The lake's Five Finger Point peninsula also includes a scenic trail. The Bearcamp River property in Ossippee is another of Eisenhaure's favorites.

Some areas, like the nearly 500-acre Lovell River property, are primarily managed for timber, research and wildlife, rather than for recreation. "The overall purpose," says Eisenhauere, "is to manage our forests sustainably. The money we make on harvesting goes directly into maintaining trails for public use on our other properties."

For more information, call (603) 862-3951, e-mail woodlands@unh.edu or visit http://www.unh.edu/woodlands/ index.html.

Page: Prev 1 2 3Easy to print version

blog comments powered by Disqus