|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

New Kids on the BlockPage 3 of 5

Kathleen Littleton, a Baltimore-area native who stood out as one of the leaders in Hiley's class, is hampered in Durham not by the coursework or socialization headaches, she says, but the feeling she is not doing enough. At home in Maryland, she worked at an organic food co-op, was active in numerous community groups, and was a 4-H club officer with responsibilities for the well-being of numerous sheep and pigs. At UNH she finds it distressing that she has so much time on her hands after classes and hasn't figured out a way to contribute to the causes she believes in. She almost wishes professors talked more, classes lasted longer, because then she could ignore how trackless she eels. "My mom keeps telling me to be patient, but it is hard," says Littleton, who is dark-haired and deceptively casual appearing with a hand-woven "hippy" shell choker. "I really beat myself up."

Omer Aktas '09

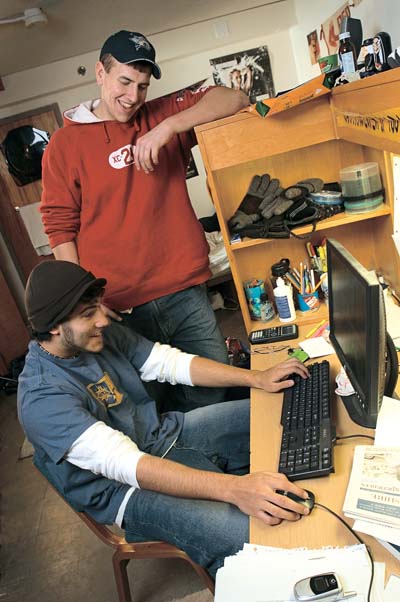

Omer Aktas '09(Above, with roommate Jeffrey Kaste '09) He grew up in a firm Muslim household without some of the customary distractions like, say, cable television. |

Jeffrey Kaste's choices are the kind the dean's office likes to hear about. A freshman from Timberland High School in Atkinson, N.H., Kaste is goal-oriented, bright and disciplined. He has managed to master time management in a way that most of us never will. He has a slate of early morning classes, a short lunch break, then track and field practice for much of the afternoon. He hasn't missed either a class or a practice. In the evening he studies, but rarely, he says, past 11 p.m. He appears the gentle giant—mammoth-sized in a de rigeur collegiate outfit of hooded sweatshirt, ball cap, carpenter pants and iPod. "I haven't been homesick or anything," he says. "I've only been down once really—when I got a C minus on a German exam. I moped around for a day, then talked to the professor and straightened myself out." The only thing freshmanlike about Kaste is his aversion to walking (he chose Williamson Hall but fantasizes for the proximity of Stoke).

Watching Kaste in Lieber's "Words" class is like watching the freshman you wish you were. He is front row, engaged and energetic. When a classmate two seats over completes a strenuously syllabicated guttural sound, Kaste is so overjoyed he throws out his oversized throwing arm to knock knuckles and comes within a whisker of socking the person next to him. "Oops, sorry about that," he says."

Kaste's roommate comes from the same high school, but finds himself grappling with more typical freshman problems. Omer (pronounced O-mar) Aktas, a chemical engineering major, doesn't take care of himself as well, loses focus and has struggled to find his groove. They couldn't be having two more different experiences. When I make arrangements to meet up with Aktas, he blows me off. Now that's the sort of thing I would've done. When we do meet up weeks later, he has the sniffles and confesses he has just blown off calculus.

He shakes his head and says first semester has been a "real kick in the back of the knees." The transition hasn't been easy. He is shy, a self-proclaimed mama's boy who grew up in a firm Muslim household without some of the customary distractions like, say, cable television. His voice barely rises above a whisper and he has a sweet, affectionate smile that makes you want to root for him. "I was studying the other day for a big exam," he says, "when I suddenly found myself doing things on the computer and plugged into music and it was like, 'Hey, wait a minute.' I had to shut it all down."

The sheer volume of freedom has thrown him for a loop. On a personal level he has held the line: He doesn't drink or smoke, in accordance with his religious principles, and he will do practically anything to keep his mother happy, including allowing her to decorate his room with cloud pillows and flower blankets. But he loses time to computer games and tends to have trouble when it comes to exams, never having developed good study habits and being a little too bull-headed to change easily. In his first calculus exam, he walked in with confidence and walked out with a 45. His programming midterm wasn't much better. "I didn't study for either." He shrugs. "I never had to in high school."

|

SO MANY OF THE AILMENTS of freshman year do sound familiar—time honored in fact—but there is a new vocabulary. "Sexile," for example. This is defined as the unlucky roommate (almost always a freshman) who finds his or her dormitory door locked one day because of an intimate liaison taking place within.

The phenomenon of instant messaging has given rise to "emoticons" and "assicons," which are undeniably part of the cyber freshman experience. If your child or grandchild calls one day having received (_?_) you would want to offer quick assurance that he or she is not, in fact, a "dumb ass."

High-tech equipment, so promising, has not helped the misunderstandings that sometime arise between freshman roommates, says Aaron Koepke, the hall director at Stoke. There is a tendency not to confront roommates face to face, he says. Now, more often than not, the aggrieved zaps a parent with an enraged IM or cell call. It is a tendency that hall directors would like to see less of. "Back in your day I doubt you were in touch much at all," says Koepke, as we tour my old digs at Stoke Hall.

He's right. There were no phones in the room, no computers. When my roommate Brad made me a sexile within the first 24 hours, I didn't call or message anyone. And when Brad borrowed my cross-country skis without asking, I simply wrote him the meanest note I've ever written a human being. No e-mails, no IMs, no calls. We're best friends to this day. The point, Koepke says, and what he keeps hammering to students, is this: "Did you even talk to your roommate?"

To the many alums who have lived on one of its eight floors, the building we're in—Stoke—is a monument, testimony to the kind of attributes you might associate with your first few months: grit and survival. Koepke tells me that today's residents believe they have found the places in the building's infrastructure where, according to the rumor, explosives would have been planted to implode UNH's most famous "temporary housing unit." Yet it survives, without adornment. Other dorms have orbited into the freshman experience—Alexander is for undeclared freshmen only; Williamson and Christensen are all freshmen too—but somehow Stoke can never be replaced.

This year there are roughly 400 freshmen residing in Stoke. Through a window I see a student tour group being rushed past on its way to the new dining experience at Stillings. I understand. The Stoke mystique is hard to explain. "It isn't for everybody," Koepke confirms, and then pauses. "But you know what's funny is how the parents of many current students want to come back and visit. They come through all the time."

Page: < Prev 1 2 3 4 5 Next >Easy to print version