|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Tough Love

Page 2 of 3

Previous | Next

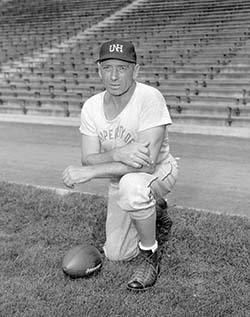

"Whenever you came off the field during a game, he would put his arm around you with his big hand on your opposite shoulder, and say, 'Now this is what I want you to do, see?' and you would do it," recalls Jere Lundholm '53, who played lacrosse for Snively and happens to be Carl Lundholm's son. "He was a disciplinarian, but he had a warm heart and a soft touch." That didn't mean playing for Snively was easy. His practices were often grueling—it wasn't uncommon for the lacrosse team to spend hours clearing the field of snow before practice "officially" began, and preseason conditioning drills included running through College Woods in drifts up to two feet deep. He spelled out his expectations for his players in no uncertain terms: Even if you couldn't play, you were still expected to attend practice. If you couldn't attend practice, it was because you were at Hood House, the university's infirmary, under a physician's care. If you missed practice and were anywhere else, you were off the team. One of his favorite sayings—or "Whoopsisms"—was "It doesn't help until it hurts." Snively applied the same dedication to his coaching that he demanded of his players. He was an overachiever in every way, constantly studying up on plays and techniques, and keeping close tabs on the competition. In his first football season at UNH, he was asked to scout St. Lawrence before a big game. He did, and wrote up a 21-page report that included "everything except what the players ate the night before the game," according to John "Doc" Enos, who profiled Snively in a 1962 piece for The New Hampshire Alumnus. The Wildcats went on to beat St. Lawrence by a whopping 34 points, though the teams had been ranked as evenly matched, and afterward the players presented Snively with the game ball, crediting his diligence with securing their victory. That dedication came in particularly handy in 1962, when Snively was asked to take over as head coach for the men's hockey team: not only had he never played the sport (despite having served as freshman coach at UNH and Williams), he'd never so much as learned how to skate. Instead, he had studied hockey by watching the Boston Bruins practice and taking copious notes. He instructed his players on skating methods in meticulous detail while he himself shuffled around the rink in oversized galoshes.

"He certainly knew more about it than any of his players did by the time he was coaching us," says Dick Lamontagne '63. "We were all wondering how he came to know the sport so well." He also put his own mark on the sport, incorporating football and lacrosse tactics into plays that caught other teams by surprise. Lamontagne remembers one as an adaptation of a football punt play in which a player in trouble would flip the puck high into the air; one of the offensive wings would then rush to pick it up. "It didn't work every time, but it's a play you don't usually see," Lamontagne explains. "In fact, I don't think I've ever seen it done before or since." Although Snively diverged from his family's tradition of pursuing medicine, he brought his father's brown leather doctor's bag—filled with piles of notes and paperwork—to every practice and game. It's not hard to see a symbolic connection between his coaching and the practice of medicine. Each season he handed each player his "Rules for Lacrosse," a 15-page document that was part sports strategy, part philosophical treatise. The players called it "Whoop's Bible," and they were expected to memorize it and follow it to the letter. In a section devoted to time management, Snively advised student athletes to prioritize their studies and keep their grades up, emphasizing that this was the best way to guarantee a bright future. He checked up on his players to be sure they stayed on track, and arranged tutors for those who fell behind. Those who still couldn't keep up with their schoolwork—including some of his best players—were kicked off the team. |

blog comments powered by Disqus