|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

Public TreasuresUNH's Very Special Collections

By Suki Casanave '86G

Photography by Perry Smith

|

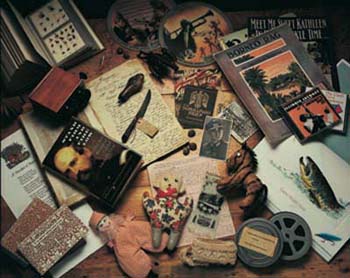

The letter, postmarked 1836, is written on pale, pink paper, nearly translucent with age. Each line of minute script seems impossibly perfect, penned by the steady hand of a Shaker elder. There are other things, too: A trout, every scale depicted in vivid detail. A knife with a musket ball impression in its handle . A toy zebra, its eye catching the light as if winking.

Gathered on a table in Dimond Library's Special Collections, the assemblage is both fascinating and mysterious, a sort of kaleidoscope of history. Each item has its own story to tell about another place, another time. And each one is here, available for study, because someone, at some point, became captivated by these stories--and wanted to share them.

The best way to understand Special Collections, with its more than 100,000 published items and more than 300 manuscript collections, is to visit--in person or online. Those who do, for research or purely out of curiosity, can touch the past. Students open medieval chant books, observe the texture and gleam of magnificent Scheier pottery, read letters written by Civil War soldiers under fire. "It's not just information they are getting," says Bill Ross, director of Special Collections. "It's a process they are experiencing."

In this sense, Special Collections is a gathering place full of shared stories and intersecting lives. The words of Robert Frost, the sound of Duke Ellington, the music of Amy Cheney Beach--they are all here, alive still. The donors themselves are the "hosts," introducing scholars of today to people of the past. Here in the hush of a sunlit room, acquaintances are made, ideas are discovered. New stories begin.

INTO AFRICA

The Margaret Carson Hubbard Collection

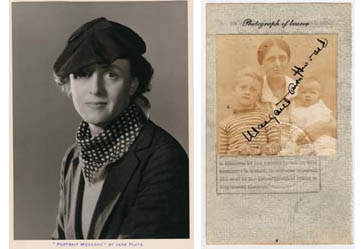

Photos of or by Margaret Carson Hubbard: at left, in a passport photo with sons Davy and Joe. Her collection, like much of UNH's Special Collections, can be searched online at http://www.izaak.unh.edu/.

Photos of or by Margaret Carson Hubbard: at left, in a passport photo with sons Davy and Joe. Her collection, like much of UNH's Special Collections, can be searched online at http://www.izaak.unh.edu/.

|

It was October of 1922 when Margaret Carson Hubbard arrived in Tara Siding, northern Rhodesia, a village she described as the "merest speck" on the vast African veld. She and her husband, Wynant, had come to collect big game for American zoos. Two days after settling into a mud hut, Carson Hubbard gave birth to their second child, Joe, while one-year-old Davy slept nearby. And so began her sojourn in the wilds of Africa.

For the next several years, while her husband disappeared into the bush for three months at a time, Carson Hubbard stayed home, caring for her babies--and a growing menagerie of wild animals, from lions to wart hogs. Before long, she was managing a staff of 250 Africans who were needed to attend to the 600 beasts.

|

Later, in articles she wrote for national magazines, Carson Hubbard recounted tales of her adventures: Davy napping with a pet leopard; run-ins with boomslangs, one of Africa's deadliest snakes; making cream puffs from buffalo fat and guinea-fowl eggs. In Vassar's alumni magazine, she told of handing her children off to Tickie, her "nurseboy," grabbing a rifle, and running off to shoot a lion. She was back in time to tuck the boys in bed.

After the war, she was appointed as the U.S. State Department's American vice consul in Johannesburg, a title that was actually a cover for a secret mission: her real job was to spy on surviving Nazis.

Decades later, when UNH's Doug Wheeler met Carson Hubbard, she was an elderly woman, living in Exeter, N.H. But her memories of Africa remained vivid, and he invited her to speak to his African history classes during the 1970s. "She was intelligent, hardy and tough," says Wheeler of Carson Hubbard, who died in 1989. " She was one of the most famous American experts on Africa who wasn't an academic."

Page: 1 2 3 4 5 Next >Easy to print version

blog comments powered by Disqus