|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

Cents and SensibilityBen Thompson's story of secrecy, love and outrage in 19th-century Durham

by Virginia Stuart '75, '80G

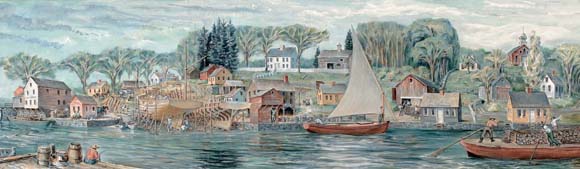

THE SPITE FENCE: In this mural painted in 1954 by the late UNH art professor John Hatch, now hanging in the Durham Community Church, the Durham waterfront of the 1820s fairly bustles. A fence built by Ben Thompson's father forced neighboring shopkeeper Ebenezer Smith to walk the long way around

THE SPITE FENCE: In this mural painted in 1954 by the late UNH art professor John Hatch, now hanging in the Durham Community Church, the Durham waterfront of the 1820s fairly bustles. A fence built by Ben Thompson's father forced neighboring shopkeeper Ebenezer Smith to walk the long way around

|

Click here for a larger view

• Read how to order John Hatch mural posters

It goes without saying that he was a man of marked peculiarities," declared the Rev. S.H. Barnum at Benjamin Thompson's funeral in January of 1890, "and they were of such a nature as to be easily observed." Thompson's relatives and Durham townspeople must have nodded in recognition, remembering the familiar sight of the miserly old man, wrapped in his shawl, riding around town on horseback. But there was another peculiarity, far less observable, that would become a source of considerable outrage and controversy once his will was read several days later.

Even today, 200 years after he was born on April 22, 1806, Benjamin Thompson remains something of an enigmatic figure. UNH historian Donald Babcock once described him as an "essential American," influenced by the intellectual movements of his era and motivated by quintessentially American values. But diaries, letters, and oral histories from the period reveal other, more personal, influences and motivations that may help explain why he did what he did—and kept it a secret for 34 years.

A photograph, upper left, shows Ben Thompson's house. Located where the Durham post office now stands, it burned in 1897.

A photograph, upper left, shows Ben Thompson's house. Located where the Durham post office now stands, it burned in 1897.

|

Benjamin Thompson was the fifth of six sons, and not only his father's namesake but also, reportedly, his favorite. He strongly resembled his grandfather Judge Ebenezer Thompson, a renowned patriot. In December 1774, the judge was one of a group of men who stole ammunition and weapons out from under the British at Fort William and Mary in New Castle, brought them back to Durham by gundalow, and hid them under the pulpit in the meetinghouse. Judge Thompson went on to become the first secretary of state in New Hampshire and a presidential elector for both George Washington and John Adams, among numerous other public positions.

As he grew older, Benjamin not only looked like his grandfather, he shared many of the same traits: a love of reading, a distaste for extravagance of any kind and a weak constitution. On his mother's side, he was descended from great-grandfather Thomas Pickering, known as "Penny Tom" for his fondness of the adage "a penny saved is a penny earned." Benjamin's mother, wrote grandnephew and local historian Lucien Thompson, was an industrious woman who was often heard to say, "I hate lazy people!"

Thompson came of age in the 1820s, when Durham was a small but thriving village of 1,200 at the crossroads between the stagecoach route from Boston and the state's first turnpike, now Route 4. The town center was perched on the bank of the Oyster River, near a gristmill, a sawmill and two boat-building "ways." Between 1776 and 1829, 75 ocean-going ships were built in Durham, including two privateers for the War of 1812.

Many residents were farmers, and John E. Thompson (no relation), in his remembrances of the period, expressed sympathy for tenants who farmed "to the halves," splitting crops with their landlords. He estimated that fully three-fifths of the town's land was thus farmed. Benjamin Thompson's father was the landlord of at least two of these farms and also owned one of the 13 stores in Durham at the time.

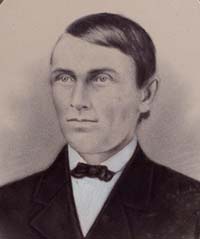

Ben Thompson as a young man.

Ben Thompson as a young man.

|

According to John Thompson, many of these stores sold little but salt fish, rum and molasses; yet "they afforded good idling places for men of small means to drop in and crack jokes, sing rude songs, drink rum, and go home at night. . . gloriously drunk." Villagers socialized at huskings, quiltings and annual muster. At purely social gatherings, young people enjoyed popping corn and toasting seeds on a hot shovel for "marriage signs."

Whether or not he ever tried to divine his marital prospects in toasted seeds, the young Benjamin Thompson apparently was looking to marry. At 20, he courted Sophia Haven of Portsmouth and even proposed to her, only to learn that she had just become betrothed to another.

After receiving his education at a village school and Durham Academy, Thompson served briefly in the state militia and taught school for at least one winter. In 1828, when his father offered to give him one of his farms, known as the Warner Farm, and two other tracts of land, Benjamin agreed to accept this gift—but only if he could receive the deed right away. He had observed what happened to the widow of an older brother who died without the deed to land their father had given him.

Thus Thompson, shrewd at the age of 22, assured his ownership of the land he would farm for the next 60 years. Having learned bookkeeping in his father's store, he began a lifelong habit of keeping account books. From 1828 till 1889, a year before he died, he filled ledgers with hundreds of pages of detailed records.

That same year, Benjamin's niece, Mary Pickering Thompson, began going to school—at the age of 3. Education at Mount Holyoke Female Seminary became her ticket out of Durham, which she later called "that prehistoric place." In addition to some modest investments, she would make her living by writing, publishing more than 130 articles. Mary also wrote hundreds of pages of letters and diary entries devoted to her passions—literature, art, religion, and, ultimately, the envy of her uncle's wealth.

Page: 1 2 3 4 Next >Easy to print version

blog comments powered by Disqus