|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

Cents and SensibilityPage 3 of 4

SHOCKING: In 1847, Mary Pickering Thompson asked to be released from the Durham Congregational Church to join a church in Kentucky, but the minister refused because Kentucky was a slaveholding state. Incensed, she joined the Catholic Church instead and became a nun. Back in town two years later, she was harangued by her former minister for being "unchristian," but honored by her uncle Ben with a party.

SHOCKING: In 1847, Mary Pickering Thompson asked to be released from the Durham Congregational Church to join a church in Kentucky, but the minister refused because Kentucky was a slaveholding state. Incensed, she joined the Catholic Church instead and became a nun. Back in town two years later, she was harangued by her former minister for being "unchristian," but honored by her uncle Ben with a party.

|

At the time when he wrote his will, Thompson was clear about his goals, if somewhat short on money. Over the next 34 years, he quietly became richer and richer, and at the time of his death, his estate was valued at approximately $400,000, about $8 million today. He also, for the most part, kept quiet about his intentions. He did correspond with the New Hampshire-born head of the National Agriculture Society, Marshall Wilder, who had founded MIT and the Massachusetts Agricultural College (now UMass). Housekeeper Lucetta Davis, acting as his secretary, certainly knew, as well as the executors of his will. But he stood quietly by as New Hampshire founded its first land-grant college in Hanover "in connection with" Dartmouth College in 1866—a connection that became increasingly uneasy—and as the people in his own town came increasingly to look upon him as a miser.

We will never know for certain how the presence of a wife and three stepchildren might have affected Thompson's ability to amass a fortune over the second half of his life, not to mention his desire to dedicate that fortune almost entirely to the goal of bringing science to farming and bringing farmers to college. At convocations and other ceremonies, UNH historians have naturally overlooked the love story and focused on the ideas and political movements that may have inspired him. Nevertheless, local storytellers have connected the dots without hesitation: Love was lost and supplanted by a lifelong, largely secret devotion to the advancement of agricultural education, which Thompson linked in his will to the promotion of "the happiness of man, the honor of God, and the love of Christ."

Although Thompson has mainly been remembered as a farmer who donated his farm to the university, it was as an investor, primarily in the railroad system, that he made his fortune. He began with a $6,000 inheritance from his parents, and at his death the two most valuable components of his bequest were railroad stocks and railroad bonds. "Thus while he rarely left Durham," wrote UNH history professor Philip Marston, "he nevertheless participated in the expansion of the United States."

As long as his health allowed, he also went to the railroad station on horseback every day—tall, spare, wrapped in his shawl—to watch the train come in. At the station, he would often place five pennies on the ground and cover them up by scuffing the dirt with his shoe. Then he made a proposal to any small boys who were around: They could keep the pennies, but only if they uncovered every one. When he caught small boys misbehaving, on the other hand, Thompson might threaten to haul them off to the Dover jail. In fact, the Rev. Barnum ruefully acknowledged in his eulogy that some people in town enjoyed provoking Thompson, who was known for his "explosive temper and profane habit."

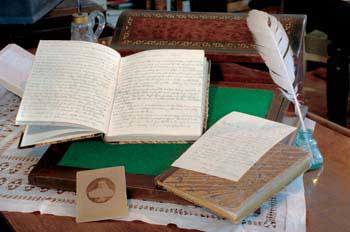

Mary Pickering Thompson wrote about her travails in diaries.

Mary Pickering Thompson wrote about her travails in diaries.

|

It wasn't just on the 5-cent level that Thompson liked to use his gifts as a kind of challenge grant. He offered to donate $100 to the town library, but only if the citizens contributed $400. For many years he donated his entire hay crop to the library association, as long as the association took responsibility for cutting, pressing and shipping the hay. And when a man was killed in a railroad accident, Thompson donated his apple crop to the man's family, provided the railroad company would ship the crop to market for them.

Rev. Barnum dryly described Thompson's "benefactions" as "perhaps not large compared with his wealth" and also suggested that envy of his wealth contributed to ill feeling toward him around town. While Thompson was growing wealthier and wealthier, the town was losing industry and commerce, and by 1860, its population started to dwindle. Niece Mary, who lived diagonally across the street from Thompson, took his lack of generosity very personally.

PREDECESSORS: This early scene of cows grazing on campus is looking northwest from the ravine, with Conant Hall in the rear.

PREDECESSORS: This early scene of cows grazing on campus is looking northwest from the ravine, with Conant Hall in the rear.

|

In the late 1870s, as she reached the half-century mark, Mary spent four years traveling around Europe, and recounted the joys of European art and culture in letters to her niece and sister-in-law. The letters were peppered with exclamations like "O for a mint of money!" or "Oh, for some of Uncle Ben's money to enable me to stay another year!" Ironically, not only did she stay another two years without a penny from Uncle Ben, she also managed to experience all the wonders of Europe on a tight budget, even if it meant scaling the cone of Mt. Vesuvius on foot while a wealthy woman was carried up in a chair.

The revelation of the contents of Benjamin Thompson's will in February 1890, caused something of an uproar, and not just among his heirs, some of whom promptly took their grievance to court. The state had two years to decide whether to accept the gift with all its stipulations, including the requirement to build an agricultural college on Thompson's farm; to appropriate $3,000 every year for 20 years to support that college; and to guarantee 4 percent compound interest on those appropriations as well as the estate. Otherwise, no bequest. Instead it would be offered to Massachusetts, and if that state turned it down, to Michigan. He did leave his housekeeper 20 shares of bank stock and all his household furnishings and belongings, valued at $1,000.

Page: < Prev 1 2 3 4 NextEasy to print version