|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

Standing in Two WorldsImmigration spurs a complex and, some researchers argue, beneficial worldwide network

by Suki Casanave '86G

photography by Lisa Nugent

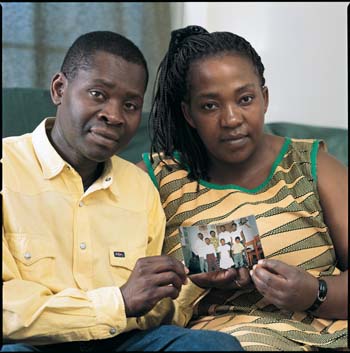

Hubert Wetemwami and Helene Muyumbu hold a photo of their children, who remain in the Congo.

Hubert Wetemwami and Helene Muyumbu hold a photo of their children, who remain in the Congo.

|

H

ubert Wetemwami will never forget the machete. It came through the early-morning darkness, a lethal shadow, swinging at his head, his abdomen, his groin. With his bare hands, Wetemwami tried to shield himself from the blows. His wife, hiding under the bed with the children, clamped her hands over the mouths of the youngest ones to stifle their cries. When the invaders had beaten Wetem-wami unconscious, they finally left.

Today, the former human rights worker tells the story of his native Congo, where the saga of violence continues, to anyone who will listen. Wetemwami now lives in Manchester, N.H., where he can walk the streets safely. He studies English, labors at a factory job, and comforts his wife, who weeps often. But he cannot hug his children, who remain in the Congo, living with their elderly grandmother. For more than a year, Wetemwami and his wife, Helene Muyumbu, have had only telephone communication with their seven children, all under the age of 18. They are never certain of their safety. "The pain of separation," says Wetemwami , "is indescribable."

As he and his wife work to adjust to their new life, they have only one goal: to reunite their family. Other immigrants and refugees have similar stories. They flee gunfire, corrupt governments, poverty. They seek safety, security and jobs. In the process, families are torn apart and beloved homelands are left behind. Those who embark on new lives in new countries are the lucky ones. But the transition is difficult, a bittersweet mix of challenge and opportunity.

About 1 million immigrants settled in the United States in 2002, as well as a smaller number of refugees (1.3 million between 1988 and 2001). At first, they speak little if any English. They have few belongings or resources. But families overseas are depending on them. Most find jobs, work hard, send money home. Many become U.S. citizens. But ties to their native land, the place they were born, remain strong. They stand firmly in two worlds.

|

"We assume you can have only one kind of identity, one kind of loyalty, but people don't work that way," says Nina Glick Schiller, UNH professor of anthropology, who together with Thad Guldbrandsen, a UNH research assistant professor, recently received a $100,000 John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation grant to study immigrant settlement and the phenomenon of transnationalism, which is essentially a simultaneous commitment to two countries.

Credited as one of the scholars who coined the term "transnationalism," Glick Schiller has given anthropologists a new way of looking at the world. "She is a leading figure in this approach to thinking about relocation across the globe," says Burt Feintuch, director of the UNH Center for the Humanities, which provided funding to Glick Schiller for a preliminary study.

The long-term results of their work, the UNH team believes, could help encourage public policies that support immigration and refugee resettlement. Even now, though, in the relatively early stages of their research, their theories have profound implications for the larger global community. "Transnational networks are holding up the world," says Glick Schiller, citing countries like Mexico, India, El Salvador and Haiti as dependent on remittances sent from families in the United States. Millions of people send money home to help feed and clothe families, provide medical care, build houses and schools, send children to college.

"If these networks of remittances were cut off, the level of human misery in the world would be drastically increased," she says. And that could have a direct impact on a much larger problem: "The causes of terrorism are desperation and hopelessness. People feel they have nothing to lose. Remittances provide hope."

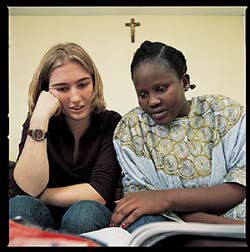

Emelia Smallidge '04 (left) tutors Victoria Yak, a resident of Manchester, NH.

Emelia Smallidge '04 (left) tutors Victoria Yak, a resident of Manchester, NH.

|

In this post-9/11 landscape of fear and suspicion, the assertion that immigrants are good for global and national security is bold and thought-provoking. "We're at a crossroads in American history," says Guldbrandsen. "We have the capacity to make the world a very difficult and very mean place. Or we have the opportunity to be a bit more enlightened and go a different route." At the very least, he says, that route should be based on accurate information about how immigrants live their lives. Gathering this data can be a painstaking undertaking. But for scholars like Glick Schiller and Guldbrandsen, this work is more than an academic endeavor, it is a calling, an opportunity to give voice to people whose life stories might otherwise never be told.

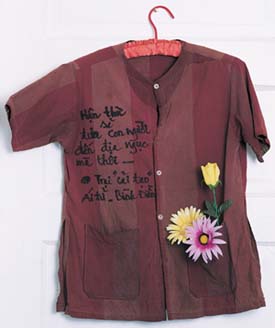

In the home of Nhat Chi Anh, just above the dining room table, a worn cotton shirt is displayed on the wall. More than a piece of clothing, it is a piece of art and a statement. Across the front, carefully lettered, is a short poem in Vietnamese--rough translation: "Hate will send you to hell." A cluster of silk flowers spills from the front pocket. The man who placed this shirt on the wall in his Manchester, N.H., home is not a collector of contemporary art. He is a Vietnamese immigrant. The shirt is his own. He wore it during his five years in a North Vietnamese prison camp following the Vietnam War. It was a bad time. He was often hungry and ill. More than once he was on the verge of death. Today the shirt he wore during his ordeal is a daily reminder that is both sobering and hopeful, a warning and a testament to the possibility of redemption.

The shirt, though, tells only part of Nhat's story, which also includes a wife and two college-age children, extended family in Vietnam, a factory job, a love of fishing, and a passion for rare orchids, which he once grew with great care in Vietnam. Today, he has little opportunity for hobbies. Nearly all of his free time is devoted to accumulating overtime at work, so that he can help to support his extended family in Vietnam.

"I've never met anyone with such a strong sense of ethics," says Guldbrandsen. "He tells me, 'I survived inhumane conditions. I escaped death in a prison camp. Why? So I can accumulate wealth and go shopping? No. So I can help people and be a good person.'"

Page: 1 2 3 Next >Easy to print version

blog comments powered by Disqus