|

|

| current issue |  | past issues |  | send a letter/news |  | address update |  | advertise |  | about us |  | alumni home |

Features

Mountain MenPage: < Prev 1 2 3

"We might have been recruited as skiers, but rock climbing proved to be the essential skill in that battle," he says. The 86th had to make its move at night because there were no trees to provide cover for the soldiers scaling its face, and one of the keys to the maneuver's success was the element of surprise. "The Germans were completely caught off guard," Bennett says. "They didn't have any idea our troops could make such a difficult climb."

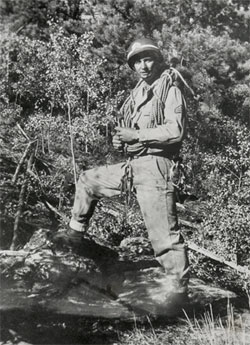

Nelson Bennett '40 perfected his rock-climbing skills at Camp Hale. Five decades after the war, he put those skills to use leading the 50th anniversary climb of Riva Ridge in Italy, summiting a total of three times. Nelson Bennett '40 perfected his rock-climbing skills at Camp Hale. Five decades after the war, he put those skills to use leading the 50th anniversary climb of Riva Ridge in Italy, summiting a total of three times.

|

At 96, Bennett still skis regularly at White Pass in Washington State, the resort where he served as general manager for 30 years. |

Ironically, in the end, a talent for skiing was the least of the skills that saw the 10th Mountain through the grueling fight for Belvedere and neighboring della Torraccia, and from there down the northern Apennines and into the Po Valley, where in mid-April they cleared the way for the U.S. Fifth Army to advance, securing Germany's defeat. Instead, the relevant tools were rock and mountain climbing, winter survival skills, quick thinking, determination and luck.

Mansfield, whose company was in reserve for Riva Ridge and Belvedere and led the attack on della Torraccia, acknowledges more close calls than he can count. Once a German bullet took off his belt buckle; his pants fell down and he tumbled into a trench on top of a dead German soldier (he still has the soldier's belt he took to refasten his uniform, the legend Gott mit uns in capital letters across its age-tarnished buckle). Another time he fell asleep on his feet, forehead against the trunk of a tree, barely registering the bullets that whistled by as he slid lower and lower, exhausted to the point of oblivion after fighting for three days straight.

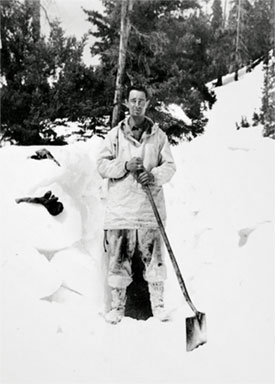

Bennett poses in front of a snow cave he built at Camp Hale. The structure served his home for several weeks during one 10th Mountain training exercise. |

"We made our first ascent of Belvedere toward della Torraccia at night, with German machine guns on our right side and snipers on our left," the 86-year-old recalls. "The cook, right in front of me, was shot dead. Men right behind me were killed, too. The fact that I wasn't ..." Mansfield, who earned a Bronze Star for his bravery at della Torraccia, shakes his head. "It was luck."

A different enemy

Bennett, too, narrowly missed death in the Italian Alps, but he faced a very different enemy. Suffering from bleeding stomach ulcers, he had become progressively weaker and thinner until by February he was no longer able to lift his rucksack. "My brother, who was in an adjacent company, found me in a foxhole and literally pulled me out, insisting I be taken to a hospital," he recalls. Down to 120 pounds, Bennett later realized his brother had saved his life. He was given a three-month medical leave and then an honorable discharge; 10 years later, his perforated ulcers were finally removed--along with 75 percent of his stomach--in a hospital in Italy, of all places. "I still joke that when I say I never got shot during the war, I mean not from the outside, in any event," he says with a laugh.

If Bennett was out of the line of fire, however, Thorne was even farther away. Although he had been hand-picked by recruiters to serve as a ski instructor at Camp Hale, because of a clerical error, he ended up being sent in January 1945 not to Italy but to Japan. He served out his commission in Shimizu, overseeing the disposal of Japanese munitions, which rolled in on as many as 100 freight cars a day. While his comrades in Europe clawed their way through the Apennines, Thorne fished for trout outside Shimizu and skied Mount Fuji---a contrast in circumstances that bemuses him even today. "I had a hell of a time," he admits. "There aren't too many other guys who could say that and mean it in a good way."

A soldier training for World War II at Camp Hale in Colorado. Photo copyright Denver Public Library. |

Singled out

Indeed, the toll the war took on the 10th Mountain was staggering. Over the 114 days during which the division was actively engaged in battle, nearly 1,000 soldiers were killed and more than 4,000 were wounded (including Crowley, the late Andy Hastings '46, '50G and the late Ralph Townsend '49, '53G), one-third of the total American casualties in Italy. Sobering in their own right, these numbers would prove to be the heaviest losses ever sustained by a full U.S. division for that length of time in combat.

The heroics of the 10th Mountain Division did not go unnoticed by Gen. Mark Clark, the Allied commander in Italy, who called the 10th Mountain the greatest unit to ever fight in that country. They also did not go unnoticed by the German Army, which saw nine of its divisions defeated on the 10th Mountain's march across the Apennines and through the Po Valley. At the German surrender, Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, Germany's ranking officer in Italy, singled out the 10th Mountain as "outstandingly efficient." Gen. Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin, commander of the Northern Italian Front, accepted the Allies' conditions of surrender only after adding a condition of his own: "I will only surrender my saber to the commander of the 10th Mountain Division," he wrote, "because of all the divisions I ever fought in World War I or II, they are the finest combat division I ever met."

Outstandingly efficient, the finest combat division. In the end, the 10th Mountain Division would not be remembered as gadabouts or playboys on skis. Far from it, they would be known as the young men who were asked to do the impossible--and succeeded. ~

See also "Snow Jobs", for an update on these and other UNH "Mountain Men", a list of others who served and a slide show of additional photos.

Page: < Prev 1 2 3

Easy to print version

blog comments powered by Disqus